Recipe management, costing, and inventory: three pillars of gastronomic success

Full house but still in the red? Many restaurateurs are familiar with this dilemma.

Full house but still in the red? Many restaurateurs are familiar with this dilemma: the restaurant is busy, guests are satisfied, but at the end of the month there is hardly any profit left. Why is that? Often, basic business principles are neglected—standardized recipes, correct price calculation, and thorough inventory management. Passion and creativity alone don't pay the bills; without keeping a close eye on costs and processes, even a well-frequented business can slip into the red. In this blog post, we highlight why recipe management, pricing, and inventory together are the key to solid margins and how they work hand in hand in practice to avoid losses.

Below, we show you in a strategic and practical way how recipe adherence, optimized cost of goods sold calculations, and regular inventory checks work together. We establish connections between recipe adherence, cost of goods sold, contribution margins, and inventory differences, and address common mistakes. The goal: clear action points to ensure that your culinary offerings are not only a culinary success, but also an economic one.

Recipe management: Precision on the plate ensures accurate costing

The kitchen is where it's decided whether a dish can be sold profitably. Recipe management means defining precise recipes for each dish with specified ingredient quantities and portion sizes – and sticking to them consistently. This adherence to recipes is not a bureaucratic end in itself, but the basis for reliable calculations: only when all chefs adhere to the specified quantities can you know the exact cost of goods per portion. If, on the other hand, recipes are "freely interpreted" and everyone cooks "their own soup" as they see fit, it becomes almost impossible to collect reliable figures on costs and consumption.

Why is this so important? Any deviation from the recipe—whether it's an oversized portion, an extra ingredient, or inefficient preparation—drives up costs. Fluctuating portion sizes between different employees lead to uncontrolled consumption and ultimately to higher costs for goods. If, for example, instead of the intended 200 g of meat, 220 g suddenly ends up on the plate, or if drinks are poured generously at the bar, the cost per sales unit increases – often unnoticed. The result: the calculated contribution margin (sales price minus variable costs) shrinks because the cost of goods sold is higher than planned. In the warehouse, such over-portioning is noticeable as shortages that cannot be explained on paper – these are referred to as inventory differences, which are often caused by a lack of adherence to recipes.

Best practice in the kitchen: Use clear recipes and portioning aids. Write down the ingredients and quantities for each dish. Modern recipe management software, such as BarBrain, or at least a well-maintained recipe book, will help you keep track of everything and quickly adjust your calculations when ingredient prices change. Train your kitchen team in uniform portion sizes—use scales, measuring cups, ladles with defined volumes, etc., to measure quantities accurately. This ensures that a schnitzel is the same size today and tomorrow and that a cocktail always contains the same amount of spirits. Standardized ml specifications per glass, for example, ensure consistent taste and less wastage at the bar. This discipline allows you to know the exact cost price of each plate and calculate prices based on this. At the same time, quality benefits: guests always receive the product they expect, and you avoid the risk of generous portions generating enthusiasm but ruining your calculations.

Common pitfalls in practice: Often, seemingly minor items are not included in the calculation—such as the dip that accompanies a burger, the bread served beforehand, or garnishes and condiments. These "invisible" costs add up. Be sure to take waste and preparation losses into account: cleaning vegetables or trimming meat produces leftovers that reduce the usable yield. Precise recipe management takes these losses into account, for example by setting higher raw material requirements or applying a calculation surcharge. If such costs are not taken into account, some of the money will be missing from the cash register at the end of the day.

In summary, strict recipe management secures the basis for calculation: you know what a dish actually costs in terms of ingredients, and you create the conditions for charging prices that cover your costs and enable you to make a profit. In addition, adherence to recipes reduces food consumption and waste—a plus for margins and sustainability.

Pricing: Calculate cost of goods sold and determine optimal prices

Setting prices in the restaurant industry "by gut feeling" or blindly following the competition is dangerous. A well-founded price calculation, on the other hand, determines the success of a business. In fact, many restaurateurs struggle with profitability precisely because prices are calculated incorrectly. The classic rule of thumb "cost of goods times three = selling price" often falls short today. Why? Because it does not take into account overhead costs, personnel costs, taxes, or fluctuations in raw material prices. For example, simply tripling the purchase value of ingredients easily overlooks factors such as the energy consumption for preparation, the time spent by the chef, or hidden costs for ingredients such as oil, spices, or side dishes. The consequences can be devastating: prices that are too low mean that certain dishes are sold at a loss without anyone noticing, while prices that are too high scare guests away. Fluctuating purchase prices (e.g., seasonal price jumps) also eat into your margin if you don't adjust them.

The right approach: The starting point for any pricing is to calculate the cost of goods sold precisely. To do this, all ingredients in a recipe must be recorded and priced down to the smallest gram—including marinades, garnishes, and even the smallest items. Use the results of your recipe management: If you know that a dish costs €4.50 in pure food costs, for example, you can use this as a basis to determine an appropriate selling price. Typically, surcharges for overheads, personnel, and profit margin are then added. An example formula from practice is:

- Cost of goods + approx. 40% surcharge for incidental costs (storage, rejects) + 30% overheads + calculated profit margin = base price

- plus approx. 17–20% personnel costs = net sales price

- plus VAT = gross final price

Such a detailed calculation ensures that all costs are covered. In practice, simpler methods have often proven to be just as accurate: many restaurants work with markup factors depending on the category. A factor of around 3.0–3.5 is often used for main courses, slightly higher for starters and desserts (3.5–4.0), and significantly higher for beverages—e.g., ~4.0 for wine and up to ~8.0 for soft drinks. These ranges reflect the fact that beverages usually have a higher gross markup than food (beverages typically have higher margins than food). It is important to find the right factor for your own concept: a simple country inn cannot charge the same prices as a Michelin-starred restaurant in the city center, where higher markups are acceptable due to higher cost structures and value.

Regardless of which calculation method you use, check your cost of goods ratio—i.e., the ratio of cost of goods to sales—regularly. This shows whether your prices are still in line. In many restaurants, a rough guideline is that a cost of goods ratio of 25–30% is healthy; anything significantly above this reduces profits considerably. In most businesses, a cost of goods ratio above 35% is already considered critical. At the same time, you should keep an eye on personnel costs; together with the cost of goods, these two largest cost blocks should ideally not account for more than around 60% of sales – this leaves enough for rent, energy, and profit. If your cost of goods ratio deviates significantly from the plan for no apparent reason, this is a warning sign (portion sizes, purchase prices, or inventory may be incorrect).

Analyze contribution margins: Professional calculation does not end with the price of individual dishes. A proven approach is to calculate the contribution margin for each item. This involves determining how much each dish contributes to covering fixed costs and generating profit after variable costs (cost of goods) have been deducted. This allows you to identify which foods and beverages contribute most to the operating result—it is precisely these bestsellers that you should promote and advertise. Conversely, you can also identify slow-moving items or products with low contribution margins that need to be reviewed. Proceed systematically:

- Determine cost of goods sold per item,

- Calculate contribution margin (selling price minus cost of goods sold),

- Rank and analyze courts according to their contribution,

- Derive measures—e.g., adjust portion sizes, increase prices, or remove items from the menu if they are not profitable.

Such data-driven decisions significantly increase the overall profitability of your menu. Menu engineering is the keyword: it's all about balance. Classic dishes such as Wiener schnitzel can be priced a little lower (a profit margin of 15–20% is common here) if higher margins are achieved on other items. Many restaurants offset low profits on some popular dishes with high profits on drinks or dessert sales—the important thing is that the bottom line margin is right (keyword: mixed calculation).

Common mistakes in price calculation: A common oversight is not promptly reflecting purchase price increases in sales prices. If, for example, the price of cheese or meat rises sharply, the calculation quickly falls behind reality without a price adjustment—the cost of goods sold skyrockets and eats into the margin. Therefore, check your calculations regularly and adjust prices or recipes as soon as costs change. Another stumbling block is "forgotten" costs. Examples include staff meals or free extras for regular guests. Such corrections should be included in the cost of goods sold calculation, otherwise they distort the figures. Shrinkage and spoilage (more on this in a moment) also indirectly affect pricing: if a certain percentage of goods typically remain unsold or are spilled in your kitchen or bar, you should take this into account in your calculations (either by setting slightly higher prices or by taking measures to reduce losses). Finally, market orientation is important: monitor your competitors' prices and your guests' willingness to pay. While you should avoid price dumping, having a feel for the market price level will protect you from losing guests due to excessive prices. The trick is to charge economically viable prices that cover your costs and generate profit without deterring guests.

Inventory in restaurants: checking stock, avoiding losses

Inventory—the regular counting, measuring, and weighing of all stock—is considered by many to be a tedious chore. In fact, smaller restaurants are often only required by law to do this once a year. But if you only count your stock once a year, you're left in the dark the rest of the time. Experts recommend conducting inventory in restaurants at least once a month—not for tax purposes, but for your own success. Why? Because kitchens and cellars often store items worth five-figure sums that could otherwise disappear unchecked. Studies show that proper and regular inventory can save up to 20% of the cost of goods. Given that the cost of goods typically accounts for ~30% of sales, this can quickly make the difference between profit and loss.

Inventory is your early warning system. It shows which goods arrived in the warehouse, how much was consumed, and what remains. If 10 kg of beef suddenly goes missing from the cold store without the corresponding sales having been made, you have a problem—either spoilage, theft, or serious calculation errors. Without inventory, you would not know where your money is going. This is because goods that should be missing but have not been sold represent a direct loss of potential sales. Regular stocktaking reveals such sources of shrinkage: spoilage due to incorrect storage, waste in the kitchen, or unauthorized withdrawals by employees. If, on the other hand, stocks are never checked, shrinkage and theft often go undetected – and the cost of goods sold creeps up above the calculated level.

Revealing weak points: An inventory compares the target stock according to the accounts (what should be available according to purchases and sales) with the actual stock (what is actually on the shelves). Differences are recorded as stock changes—for you, these are tangible losses. Causes can include recording errors, theft, or incorrect counting. Typical problem areas: the bar (keyword: bar loss), perishable goods in cold storage, or high-priced products such as spirits and steaks, where even small quantities add up to a lot of money. Especially at the bar, losses are almost part of everyday life: beer foams over, a glass tips over, shots are poured generously or given on the house. The tax office recognizes a flat rate of 3–5% for bar losses – it shouldn't be any more than that. But when no one is looking, free rounds and over-pouring can easily drive losses into double-digit percentages – drastically reducing your beverage profits. Regular inventory checks (weekly partial inventory checks for expensive spirits, if necessary) create transparency here. This allows you to determine, for example, if two bottles of vodka are "disappearing" per week and react accordingly.

Practical tips for inventory: Make inventory taking a routine and part of your company culture. Set fixed intervals and responsibilities. At Cosmo Burger, for example, inventory is taken on the same day every week before new goods are ordered—this is the most efficient way. Work in a structured manner with checklists so that no area is forgotten (think of the freezer in the basement, the opened bottles at the bar, etc.). It is advisable to count in pairs at least: four eyes see more than two, and by separating responsibilities (e.g., someone from the service team counts the bar, someone from the kitchen counts the warehouse), you reduce the risk of manipulation or cover-ups. New deliveries should be set aside on inventory day and only put away after counting so as not to distort the stock figures. During the inventory, make a note of any unusual items: expired goods, damage, or excess stock.

Nowadays, digitalization can make life considerably easier: there are inventory management systems that link the cash register and stock levels. This means that every sale is automatically deducted from stock; when a minimum stock level is reached, the system reminds you to reorder. Such tools provide reliable reports at the touch of a button, highlighting potential savings. But even with simple tools—such as Excel lists—you can achieve a lot, as long as you do it consistently. It is important to analyze and use the inventory results instead of filing the list away unread. Ask yourself: Does the consumption of goods correspond to expectations based on sales and recipes? Where are there anomalies? Perhaps the serving loss is higher for a certain employee—a signal for training or stricter controls. Perhaps certain ingredients are regularly left over—a sign to adjust purchasing behavior or revise the menu.

Ideally, the findings from the inventory should flow directly back into your business management. By identifying weaknesses at an early stage, you can take countermeasures: improve purchasing processes, optimize warehousing (e.g., according to the FIFO principle: first in, first out, to minimize expiration) or adjust recipes if you notice that too much is being cooked on a permanent basis. This reduces waste and saves money. In short, regular inventory gives you control over the entire product cycle—from purchasing to storage to sales. The result is reduced product costs, a more organized warehouse, and ultimately a reassuring feeling that "nothing falls through the cracks."

Interplay between recipe compliance, cost of goods sold, contribution margin, and inventory differences

Now that we have looked at each of these three areas individually, the question arises: how do recipe management, pricing, and inventory interact? The answer: like cogs in a clockwork mechanism—the system only works efficiently when everything runs in sync. In the restaurant industry, the cost of goods sold is the key figure that connects these areas like a common thread. It shows how much money you actually spend on goods to produce food and beverages. It therefore reflects how consistently the kitchen calculates and works, how well your pricing strategy is working, and how much loss occurs in the warehouse.

Adherence to recipes has a direct impact on the cost of goods: if recipes are followed precisely, the cost of goods per portion remains within the planned range. The contribution margins per dish then meet expectations and your preliminary calculations are accurate. However, if recipes are not followed, the cost of goods per unit increases (e.g., due to additional consumption of ingredients) – resulting in lower contribution margins and, in aggregate, a higher cost of goods ratio. This is reflected in the inventory in the form of stock differences: the quantity consumed is greater than expected based on sales figures, meaning that goods are missing from stock. A practical example: Let's assume that your kitchen team does not strictly adhere to the 150 g pasta portion specified in the recipe and generously puts 170 g on the plate. That's 20 g "too much" per portion. If you sell 200 pasta dishes per month, 4 kg of pasta disappear above plan. However, your recipe calculation was based on 150 g, so the cost of goods for this dish is about 13% higher than expected. Your contribution margin per serving shrinks accordingly, and in the monthly inventory, you have 4 kg less pasta in stock than you should have according to your calculations—a classic inventory difference caused by a lack of recipe adherence.

Pricing and inventory also interact: Correct price calculation first requires correct cost of goods values (which are determined by recipe management). At the same time, a regularly calculated cost of goods ratio helps you keep your prices realistic. If the inventory shows that the cost of goods is, for example, 33% of sales, you can check whether your prices are still correct—you may need to readjust them to get back to, say, 30% and achieve your target margin. Conversely, if your cost of goods ratio remains consistently in the green, this is an indicator that purchasing, recipes, and sales prices are in balance.

Ideally, this triad becomes a continuous improvement process: the kitchen provides reliable food cost data thanks to recipe adherence, controlling (or you as the boss) sets market-driven prices based on this data, and inventory checks whether theory and practice match. If there are any deviations—e.g., increased cost of goods or stock losses—you can take targeted action: Is it due to increased purchase prices? Then adjust prices or look for cheaper suppliers. Is it due to excessive shrinkage? Then optimize processes, raise employee awareness, or increase controls. Those who have their cost of goods under control can manage their restaurant in a targeted and economically successful manner. This key figure is not a dry value, but a living control instrument that connects purchasing, kitchen, and sales.

It is clear that all three components are interlinked. Neglect one of them and the whole structure begins to falter—even optimal prices are useless if the food is "overcooked" in the kitchen; strict adherence to recipes is of little help if the prices are calculated incorrectly; and careful calculations remain theoretical if, due to a lack of inventory, more was consumed than expected in the end. Only the combination of recipe management, calculation, and inventory results in a coherent system that minimizes losses and secures profit margins.

Best practices and tips for the restaurant industry

How can this be implemented in everyday life? To conclude, here are some clear recommendations that can be applied immediately:

- Introduce standardized recipes: Document the exact ingredients and quantities for each dish. Train your team to follow recipes closely—everyone must understand that 10 g more truffle or an inaccurate dash of spirit can affect the operating result. Use measuring tools (scales, dispensers) and make recipes easily accessible (recipe folder or digital tool).

- Calculate the cost of goods per dish: Take the time to determine the cost price for each menu item and each beverage. Calculate the cost of goods taking into account losses (trimmings, evaporation rate, tasting portions). This will also help you identify outliers—dishes that are unexpectedly expensive to produce.

- Set prices with a plan: Never set sales prices at random. Choose a calculation method (e.g., markup factor or contribution margin accounting) and remain consistent. Define target cost of goods ratios (e.g., "max. 30%"). Example: If a cocktail costs $2 in ingredients, you may want to charge $8 to $12, depending on your concept, to cover losses due to pour-out and operating costs. Many successful bars calculate drink prices using fixed markups (e.g., factor of 5 for spirits) – use industry values as a guide, but take your own cost structure into account.

- Regularly recalculate: Review your calculations at fixed intervals (e.g., quarterly) or when important changes occur. If supplier prices rise or new fees are introduced (CO₂ tax, VAT change), update your calculations and adjust your prices before your margin suffers. Don't be afraid to raise prices when costs increase—if necessary, communicate openly why, because guests also understand that quality comes at a price.

- Conduct monthly inventory: Ideally, conduct inventory in your restaurant on a monthly basis (more frequently for certain items if turnover is high). Plan a time when it is quiet (e.g., Sunday after closing or Monday morning before delivery). Work with systematic lists and count in pairs using the dual control principle. Record all inventory—from the large cold storage room to the smallest bottle of liqueur at the bar.

- Analyze inventory discrepancies: After each inventory, compare the target stock with the actual stock. Investigate discrepancies: Why are 3 bottles of wine missing, for example? Were they forgotten to be recorded (training issue), were they stolen (security issue), or was there shrinkage (quality issue with the supplier or storage)? Only those who know the causes of shrinkage can take countermeasures—whether through stricter controls, better employee instructions, or technical aids (e.g., dispensing control systems that enforce booking before serving).

- Involve and train employees: Make it clear to your team why these measures are important. Every chef who follows the recipe, every waiter who avoids mistakes when taking orders contributes to success. Convey that fewer losses also mean more scope for investments, employee bonuses, or secure jobs. When everyone pulls together—kitchen, service, bar—you can get the most out of it.

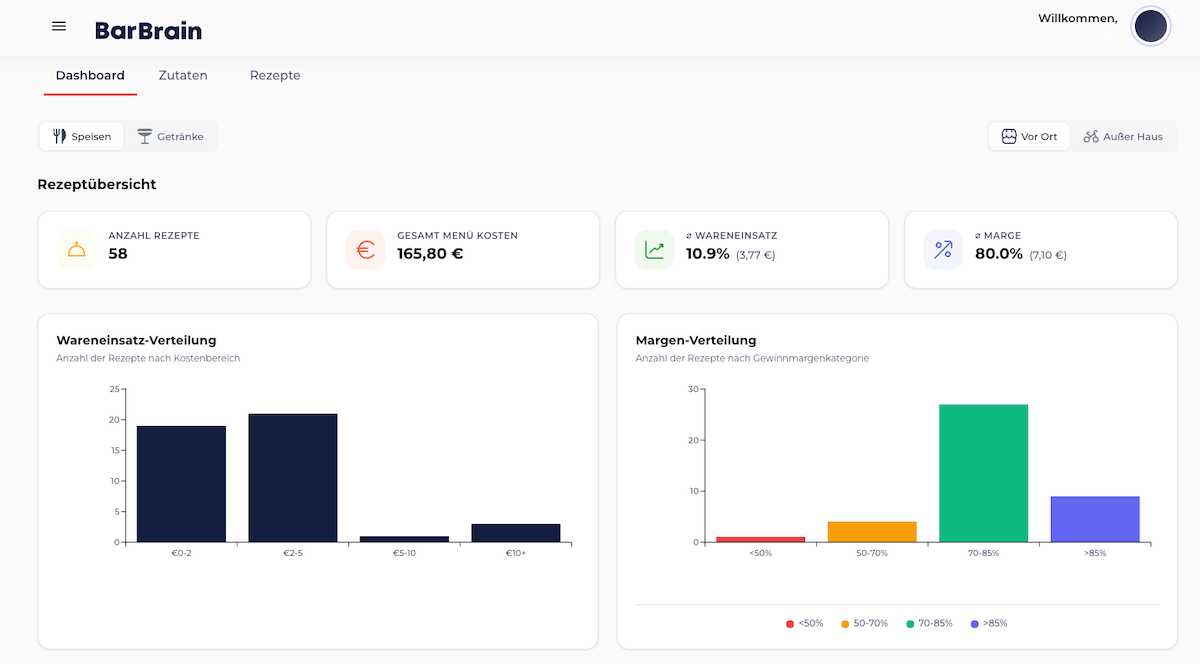

- Use digital tools: Consider investing in software for recipe management and inventory control. Digital tools take care of a lot of the calculations, automatically update prices when they change, and can compare sales with inventory levels. This makes monitoring much easier and saves time—time that you can then spend on your guests.

Conclusion: A systematic approach to sustainable success in the restaurant industry

In addition to warm hospitality and delicious food, a successful restaurant concept needs one thing above all else: economic substance. The three pillars presented here—recipe management, accurate price calculation, and regular inventory—form the foundation on which a profitable restaurant business rests. It may seem unusual at first to pay such close attention to numbers, grams, and percentages, but the effort is worth it: even small improvements in cost of goods or pricing can significantly increase profitability. And often it is precisely these "basics" that make the difference. Those who have their costs under control and know their own key figures can navigate calmly even in turbulent times – whether due to price fluctuations in the market or higher operating costs.

At the end of the day, your restaurant business should not only make your guests happy, but also ensure a good income for you as the owner. With clear recipes, fairly calculated prices, and meticulous inventory control, you can create transparency and control. The relationships between the kitchen, costing, and inventory become traceable and controllable. This allows you to make the right adjustments before losses occur. The motto is: "Maintain control before it gets expensive." If you stick to these principles, not only will your tables remain full, but your cash register will also be full at the end of the month. Economic success in the restaurant industry is no coincidence, but the result of consistent work on your own processes. So get started: calculate your cost of goods, work out your prices, and count your inventory—your business will thank you with a profit!

Book a demo now!

Do you want to improve your inventory? Then now is the time to book a no-obligation demo.